Making good on years of threats

Hey, here's a fun idea: I'm going to try to do something and probably fail miserably, and you're going to get to watch it happen.

Come on, it'll be fun!

So I was laid off in May after 19 years employed as a games journalist.

(That's not the fun part.)

And one of the things I always said I would do if I was laid off was to write a book about one of my favorite games. And as anyone could guess if they have followed my work long enough (or been trapped in an elevator with me for more than a couple floors) that game is Nippon Ichi Software's ZHP: Unlosing Ranger vs. Darkdeath Evilman.

(This won't be a book, but it will probably be more discussion of ZHP than is reasonable to publish in 2024. And I plan to write more columns on the game on this site as well, so be sure to subscribe if that is something you would like to read.)

ZHP is a game I've talked about a lot, written about a little, and never really felt like I was able to explain in the way it deserved.

Not that you really need evidence of that claim, but here's me back in my GameSpot days saying, "I really need to spend more time thinking about this to put it into words more succinctly."

That was 14 years ago.

I've told people about its goofy sense of humor, its (mostly) edifying and good-natured narrative, and its clever rogue-like gameplay plenty in the years since, but I'm still not sure I've ever figured out exactly how to properly put my appreciation of this game into words.

But that's no reason not to try.

What even is this game?

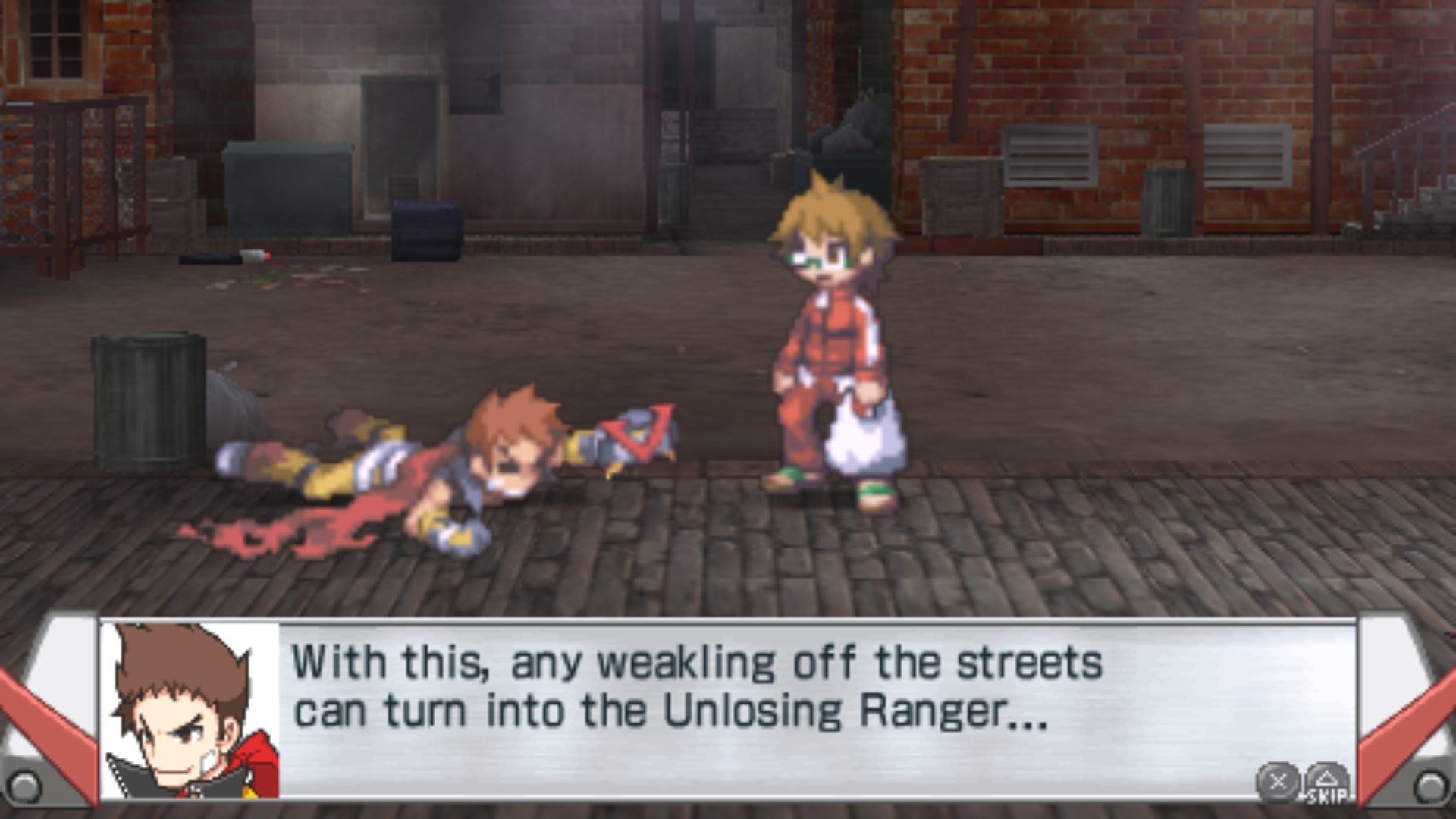

In ZHP, the Unlosing Ranger, hero to millions and savior of the world many times over, is rushing over to a climactic battle with Darkdeath Evilman when he forgets to look both ways crossing the street and gets run over by a car. His dying act is to pass the Unlosing Ranger mantle and costume onto a nearby rando, who is given the impossible task of saving the world in the Unlosing Ranger's stead.

That rando dutifully shows up to fight Darkdeath Evilman, who utterly trounces him, because our "hero" is still just a normal kid. Fortunately for the kid, that Unlosing Ranger costume comes with a single power, a belt that teleports the user to safety if they are about to die.

An instant before the killing blow, our hero is whisked away to a hero training center on Bizarro Earth, where he is put through dungeons populated with Bizarro Earth counterparts of the game's cast. There he must help fix their hearts and bring them around to the game's concept of heroism before he is deemed ready to return for his next humiliation at the hands of Darkdeath Evilman.

As for the actual game part of ZHP, it is a breed of turn-based roguelike that will be familiar to those who played games like Shiren the Wanderer, Pokémon Mystery Dungeon series, or perhaps Fatal Labyrinth. The player is dropped into a dungeon with randomly generated floors. They only have a limited amount of energy that depletes with every step or action, and they must find the exit to each floor and ultimately defeat a boss opponent at the end of each dungeon in order to escape.

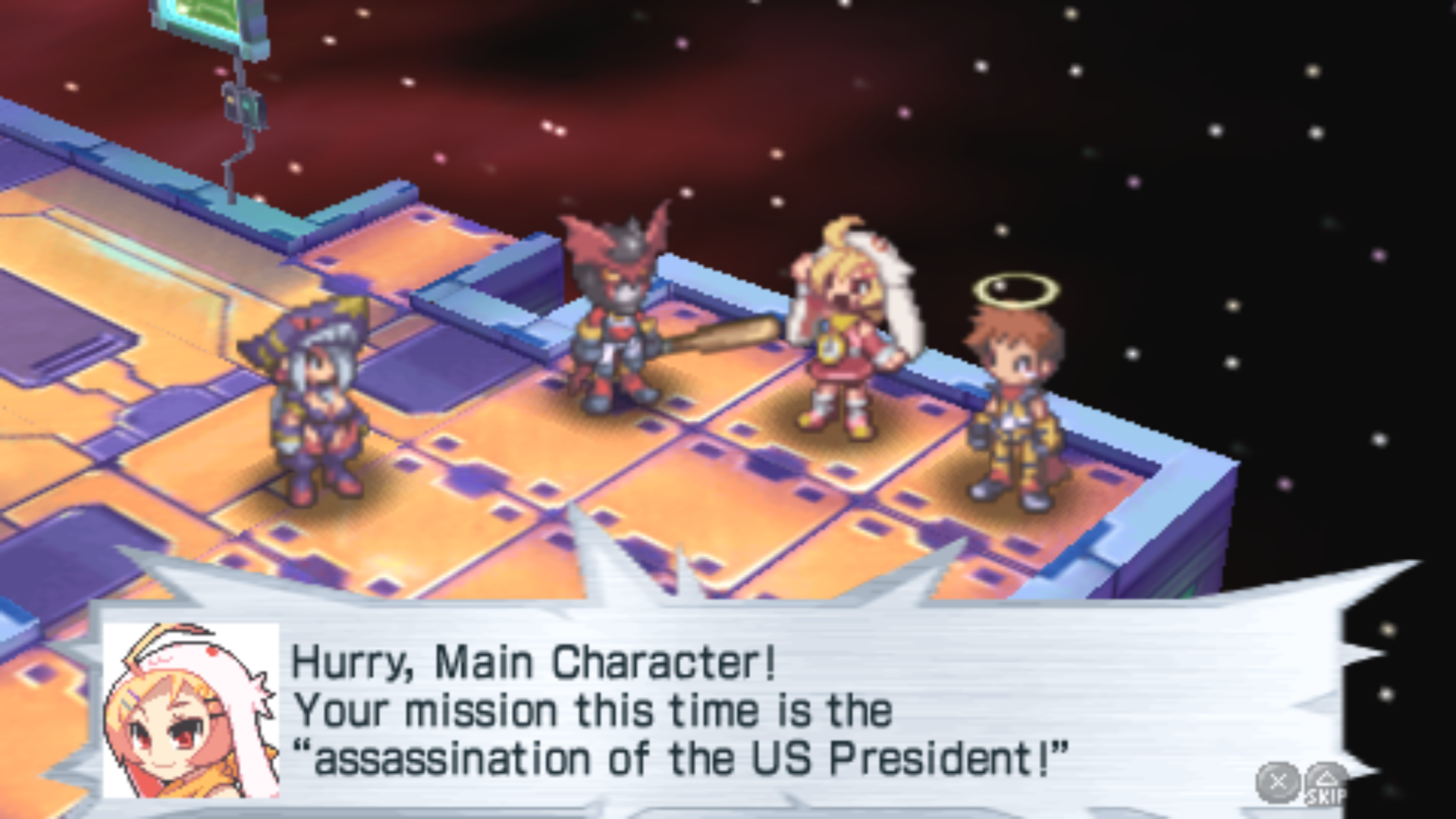

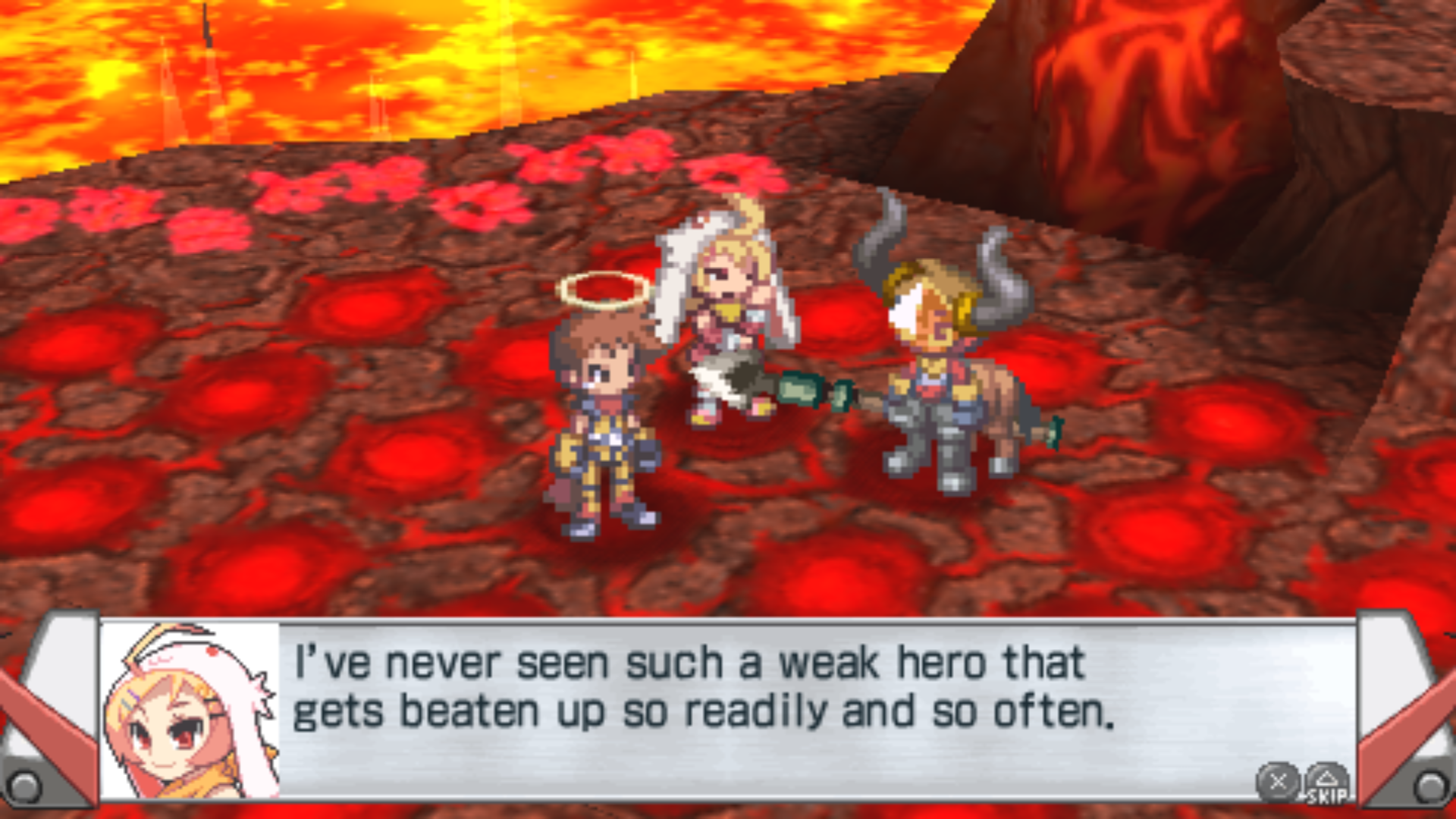

There's a huge variety of weapons and equipment to find in these dungeons (explaining why the main character looks very different from screenshot to screenshot in this article), but it all degrades with use and must be frequently repaired or replaced.

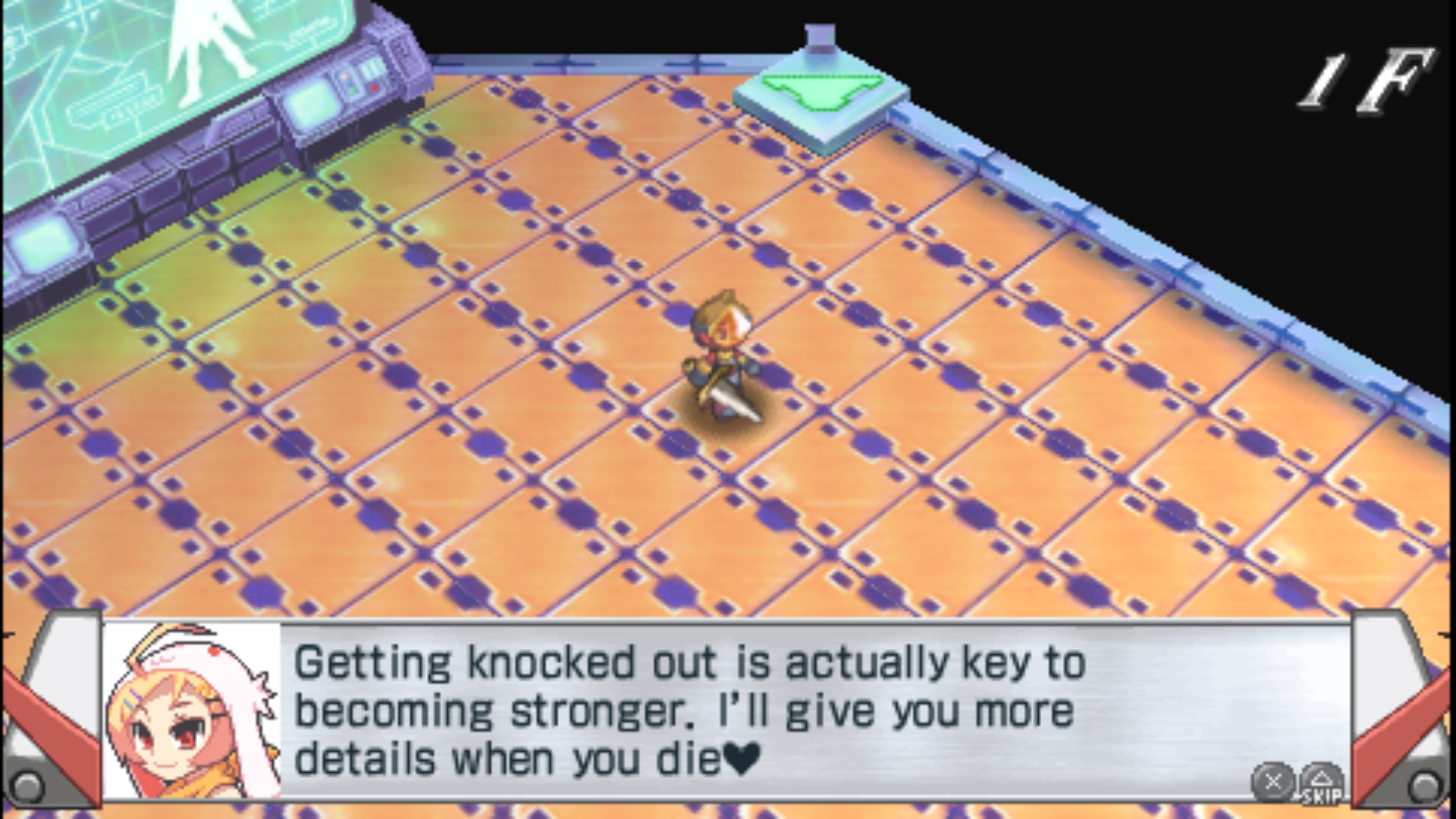

Whether a dungeon run is successful or not, the hero grows stronger with each attempt, depending on how many levels he completed and the monsters he vanquished. Unless you have problems with the very light puzzle elements in a handful of boss battles, there's no way to get stuck or halt your progress entirely. No matter how tall the obstacle in front of you may be, you can surmount it by building a mountain of your own corpses large enough to climb over (metaphorically speaking).

The only way to lose ZHP is to stop playing it. But winning is almost beside the point here. In fact, the game encourages you to make what are essentially suicide runs through its longer dungeons just because it will bolster your character progression for the next run.

Whether you're talking about the gameplay mechanics or the narrative, the readily apparent message of ZHP is the same: losing builds character.

Ask anyone who's sick to death of ludonarrative dissonance discourse and they'll tell you that kind of synergy between gameplay and narrative is uncommon, even today.

But keep in mind this game was released in 2010, just three years after the phrase first entered the public consciousness, and almost two years before Indie Game: The Movie and Steam Greenlight signaled a boom era for small game developers that saw a flood of creators experimenting beyond the formulaic confines of mass market games. It would be six long years before jokes about Nathan Drake being a sociopathic mass murderer were so hackneyed they would inspire a trophy in an actual Uncharted game.

That's not the only aspect of ZHP that, in hindsight, feels like it was ahead of its time.

Light touch, heavy subjects

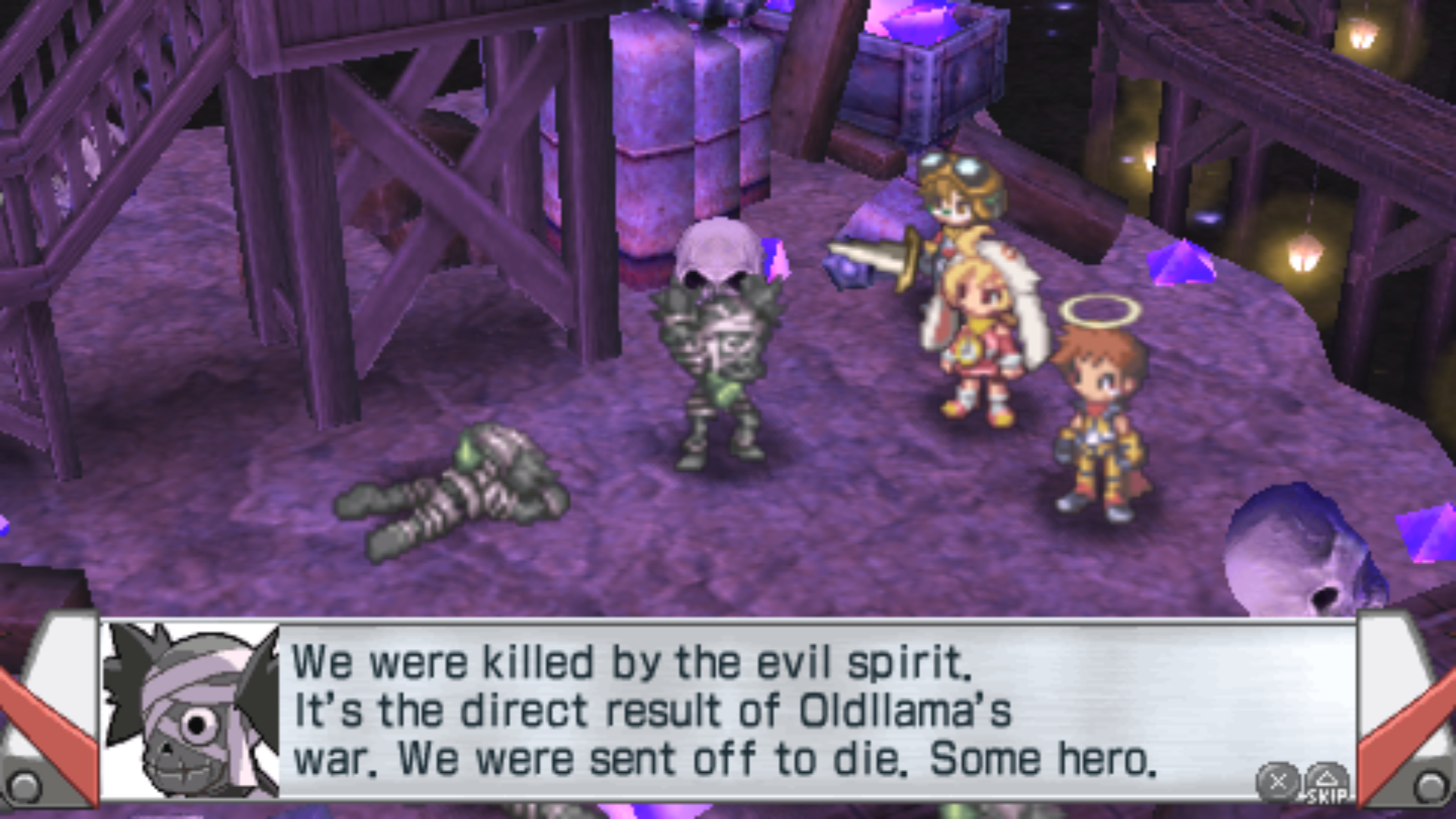

This might sound odd coming from what appears on the surface to be a silly knock-off of kids super hero shows like Power Rangers, but ZHP handled some incredibly sensitive subject matter amidst its zany hi-jinx, and often did so in thoughtful and affecting ways.

In some ways it feels a lot like the Yakuza games featuring the character Ichiban Kasuga, in which a pure-hearted dope and his pals careen through the criminal underworld, fighting a giant squid with an over-sized sex toy one moment and then the next expertly lunging for the heart strings with stories of found families, forgiveness, lost loves and aching regrets.

And in some of its best moments, the game even meshes its two extremes together.

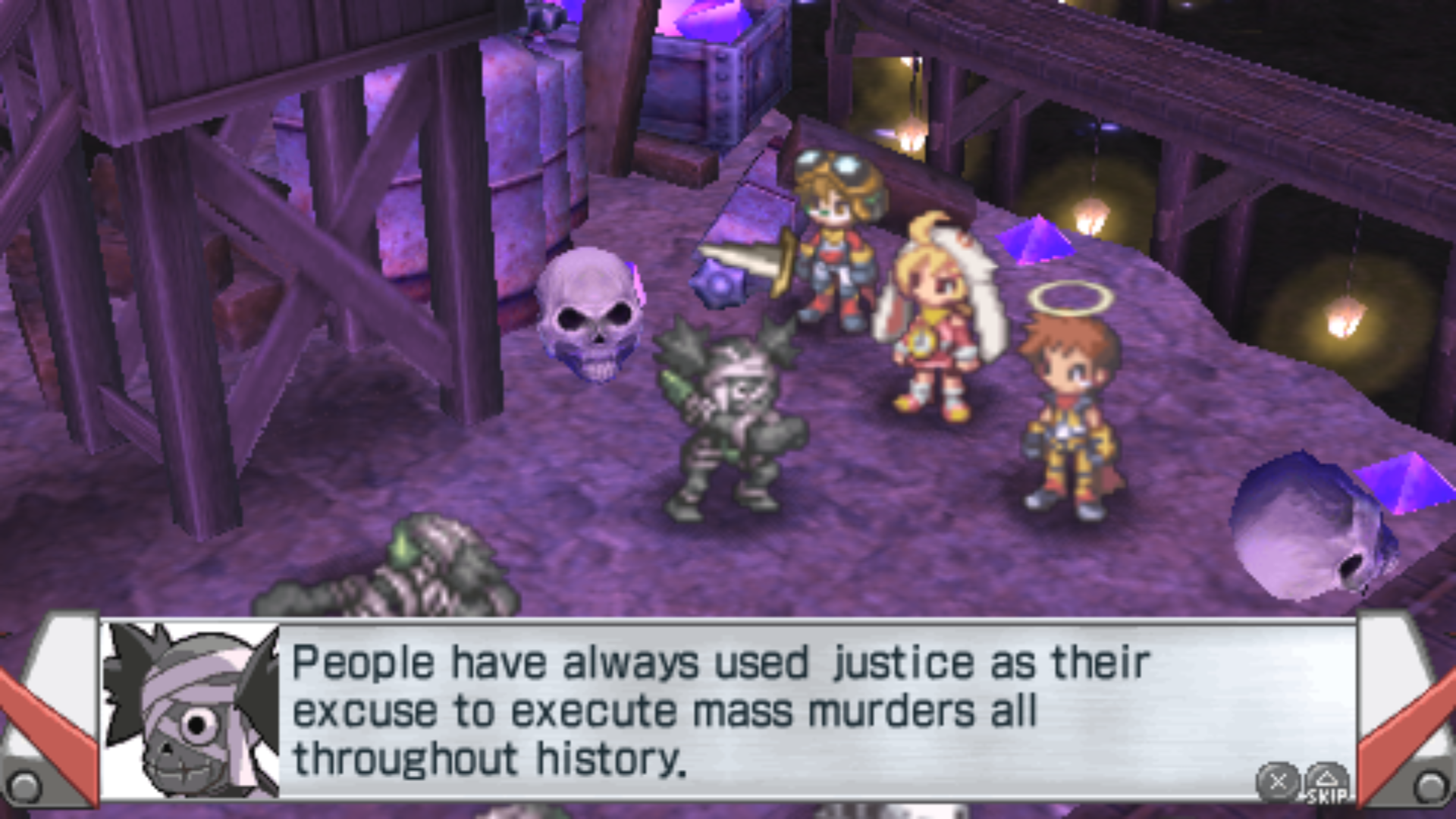

And much like Ichiban, ZHP applies the black-and-white sense of morality from the all-ages stories that inspired it to an assortment of grown-up scenarios, many of which our society has long-since accepted as morally grey.

ZHP regularly and eagerly deals with subjects that would have have been seemed out of place in the shows that inspired it: child abuse, abortion, broken families, bullying, international politics, disgruntled worker violence, war, and more.

Sometimes these things are not explicitly named or they are talked about around the edges, but they are not dodged the way we are used to seeing from publishers like Ubisoft.

Rather than avoid saying anything about such heavy subject matter, ZHP almost goes out of its way to wrap them into the story. It doesn't linger too long on most of these subjects, but regardless of how complex and morally grey these situations in real life may be, ZHP (for the most part) applies its black-and-white morality to them in understandable, reasonable, and sometimes even clarifying ways.

It's often thoughtful about these situations, noting the impact of power dynamics, personal pressures, and familial trauma, consistently showing empathy for both the heroes and villains of its deeply flawed cast in ways I wasn't accustomed to seeing in popular media of the era.

At the same time, there are a few places where it falls tremendously short of that bar, wallowing in content that is problematic at best, in particular the sort of thoughtless racist and transphobic humor that can be observed (but not excused) as a product of its time. (This is one aspect of the game I hope to dig further into in a future column.)

ZHP's super power

All of the above helps make ZHP a great game in my eyes, but it doesn't explain why I feel compelled to keep talking about it 14 years later, or why I made the name of my personal website a reference to it.

I think the reason why the game resonated with me so particularly is the philosophy of heroism that it embraces, because it is not particularly results-oriented. Too much of modern life is viewed through a results-oriented lens.

The value of going to college can be measured not by what you learned and how you grew but by whether you earned a degree that led to high-paying employment.

The value of a romantic relationship is determined not by whether you formed a genuine connection with another human being and fostered happiness and a healthy, loving partnership in defiance of an uncaring world for even a little while, but by whether it led to marriage and kids, whether it lasted until one of you died.

The value of starting your own website about video games is determined not by whether it gives you an outlet for your work and allows an audience to see it, but by whether it pays the bills.

Those "successful" outcomes are all wonderful when they happen, but they are not prerequisites for those things to have been valuable regardless.

It seems obvious, but when you think about the fictional stories of heroes our culture tells itself, it's not hard to think results are what matters. Good triumphs over evil, the world is saved, bad guy banished to an inter-dimensional prison where time does not exist, that sort of thing.

Sure, bad stuff happens so that the stakes feel appropriately high, but in the end, the heroes almost always save the day (or at least what's left of it).

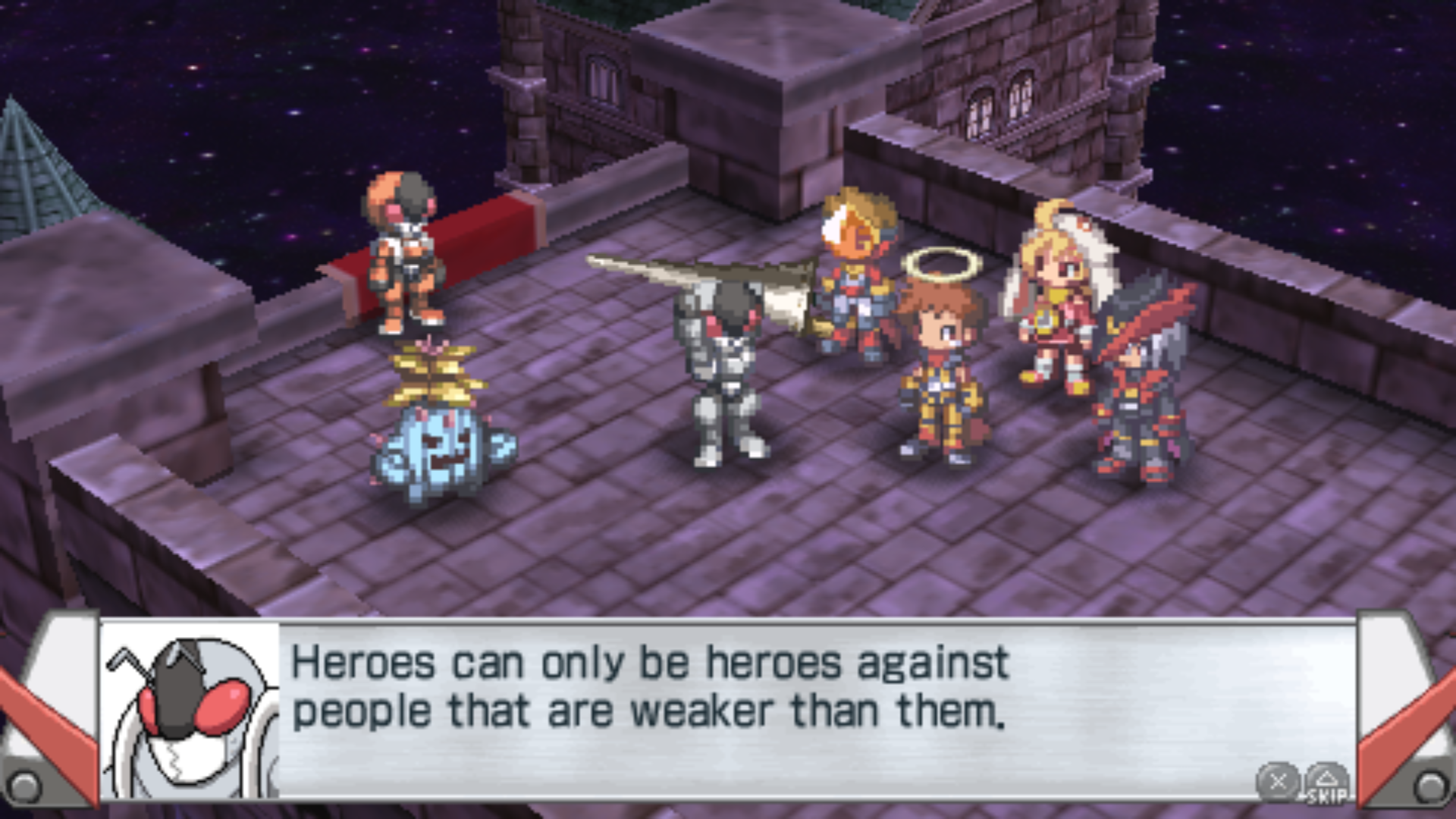

There are legitimate narrative and financial reasons for stories in popular media to adhere to that general formula, of course, but ZHP raises an interesting question about what it means when the one thing the heroes of these stories all have in common is that they win.

The closest thing ZHP has to an antagonist character, Darkdeath Evilman, has concluded that because heroes always win, they must only be picking battles they know they can win, putting them on the same ground as common bullies. His world-threatening scheme is the culmination of an effort to prove once and for all that real heroes don't actually exist, and those who claim the mantle are just in it for self-serving reasons.

The protagonist in Unlosing Ranger is (for the most part) a refutation to that view of heroism. His attempts at heroism are not successful in the traditional sense, and he is not lauded for them. He is mostly disdained in fact, even by his own family. His repeated attempts to save the earth are met with frustration by the masses, who just see him as a hopelessly overmatched loser.

He is not particularly powerful, intelligent, or cunning. He is just a person who tries his best, because he wants to do the right thing, regardless of how spectacularly he will fail, or how publicly, or how repeatedly.

The entirety of ZHP consists of the main character in a main event showdown against the embodiment of nihilism, one in which the whole world watches him lose time and again. He fails repeatedly at his efforts to save everybody, but through the Bizarro Earth training levels, he chalks up little victories, helping one or two people at a time, saving them from their personal despair before going back for another crushing defeat at the hands of Darkdeath Evilman.

In what may be the game's most actionable lesson, the threat in ZHP is simply too big, too overwhelming for any individual to handle it, even with a fancy hero belt. Attempting to grapple with it directly leads to predictable defeat. But that doesn't give the main character a pass to ignore the abundance of more manageable everyday problems he and the people in his community are facing. Those problems are ones he can actually do something about, so that's what he does.

Ultimately, this sad sack off-brand Unlosing Ranger thwarts Darkdeath Evilman's scheme and saving the world. And while that admittedly undermines some of the point I'm trying to make here, the narrative makes it clear that it's only possible because of the groundwork the hero laid along the way, the consistent efforts made to properly deal with the many smaller problems that create a sense of despair around the one big one.

The people the main character helps go on to help others, who go on to help others in turn. Even in repeated defeat, his heroism improves the world around him, creating ripple effects that eventually come back to help him save the day. It's a virtuous feedback loop that ultimately makes a happy ending possible.

Losing doesn't build character; it reveals it

While the story largely fits The Hero's Journey template, there are a few tweaks to the familiar formula.

First, the main character doesn't exactly refuse the call to action.

When the dying original Unlosing Ranger asks our woeful bystander to step into the shoes of the hero, the game pops up a dialog box letting the player choose whether to accept the request or not. But in the fine tradition of Rambo for the NES asking the player repeatedly until they agree to the game's rescue mission, it's not actually presenting a meaningful choice.

You can try to refuse the Unlosing Ranger's request, but he ignores it and the game plays out the same way regardless.

The other big deviation from the Hero's Journey – and this is something of a spoiler – is that there is no character arc for the protagonist, no meaningful change or growth beyond the RPG number-goes-up stat increases. He begins to carry himself a little more like a hero by the mid-point of the game – landing on his feet and striking a fighting pose before battle instead of faceplanting and slouching his way into the fray – and the game's other characters say he is learning new powers and growing more determined, but the heart of the character hasn't changed in the slightest.

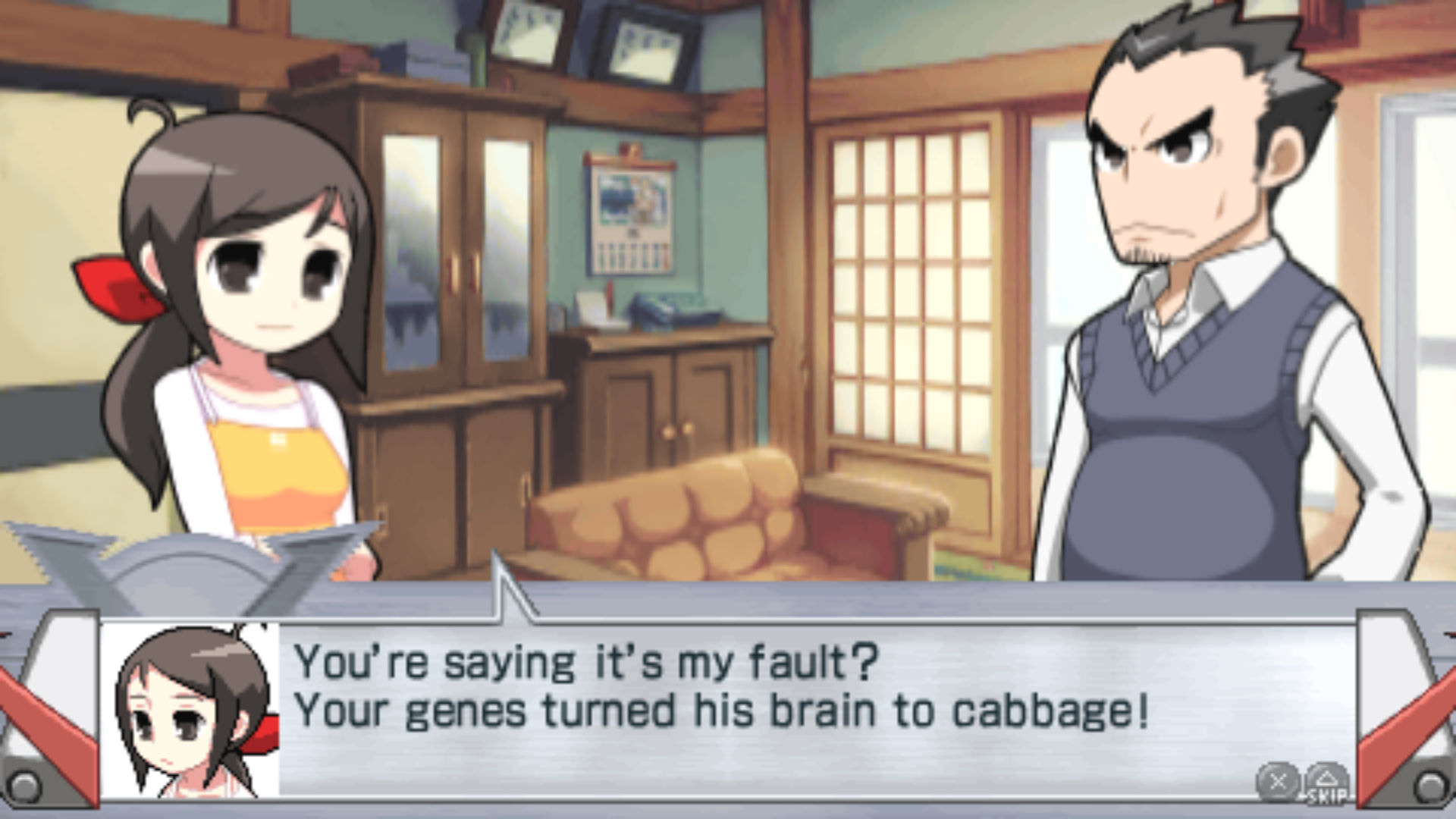

ZHP spells this out in the penultimate chapter, when it finally tells the main character's backstory, explaining why his family hates him and his parents blame him for their failing marriage. Seven years before the game's outset, the main character (then eight years old) and his sister (just three years old) were abducted by a serial killer.

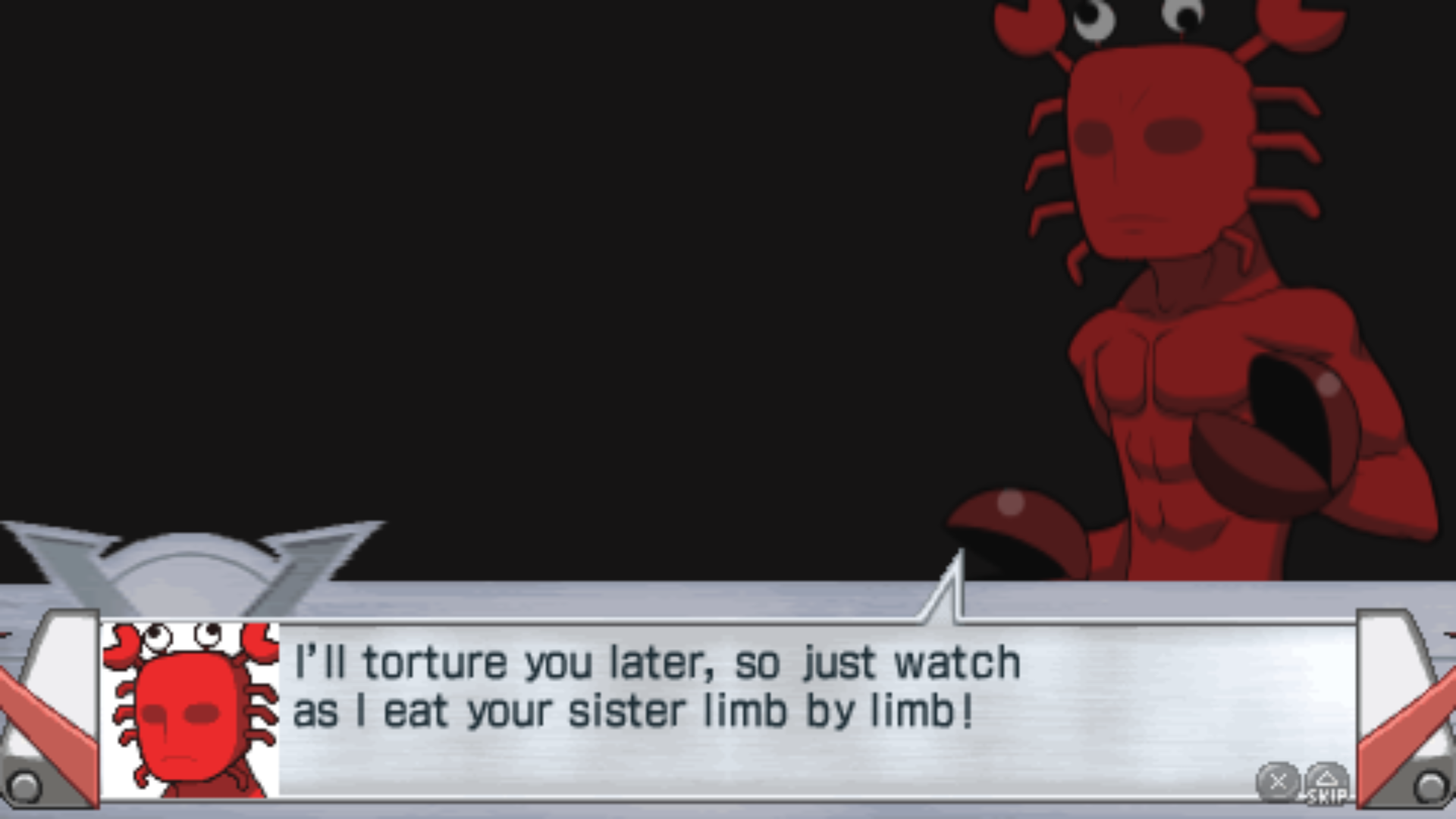

Naturally, he is dressed in a goofy head-to-toe crab costume because this game's biggest swings are tonal in nature.

When the kidnapper takes the kids back to his hideout and begins to focus on the sister, the main character intervenes physically, having all the success against a grown man that you would expect from an eight-year old whose own parents describe him as "wimpy." Despite taking a beating, he repeatedly puts himself in between the kidnapper and his sister, crying and screaming the whole time. He fails to overpower the kidnapper or escape with his sister, of course, but he does buy enough time for the Unlosing Ranger of that era to locate the hideout and save the day.

Traumatized by the event, the girl remembers just two things that she tells her parents: First, that the Unlosing Ranger rescued her, and second, that her older brother spent the whole time crying and screaming. Believing that their older child had not even tried to protect his sister, the parents begin verbally abusing him. Even the sister spends the following years demeaning her "useless" brother, as she only saw where her parents aimed their hostility as they tried to rationalize away any blame they might have for the kidnapping.

While the player can have the main character technically refuse the mantle of the Unlosing Ranger, the game eventually makes it abundantly clear that's not a choice this character would ever make. Because he was always the same heroic person at his core, even without the benefits of a belt teleporting him to safety or other heroes to train or mentor him.

A more results-oriented person might have learned better after all the suffering he endured the last time he tried to do the right thing, but our protagonist stubbornly, ignorantly, heroically refused to learn a single blessed thing. When the time came, he signed up to do it all over again just the same.

Yes, in the end the Unlosing Ranger wins, redeeming all of the game's antagonists (including Darkdeath Evilman himself) and saving the world several times over. But the emotional climax of the game clearly comes in that penultimate level, in the story of a powerless little kid who kept getting up to protect his sister and received nothing but scorn and abuse for his efforts for eight long years.

And this is where I wish the stories we tell of heroism were a little different, a little more accepting that heroism doesn't hinge on a happy ending, that doing the right thing has value regardless of whether or not it saves the day, changes anyone else's behavior, or is met with any kind of karmic reward. Because all that is largely out of our control as individuals.

I've been thinking about this a lot in the past decade or so, as I've seen world politics take terrifying turns that leave me reassessing my ideas of what a "worst-case scenario" can look like in our world, slowly reducing the number of things I keep in the "It couldn't happen here" folder of my brain.

Some days it's hard to be hopeful about the future, about the possibility of people ever remembering the lessons of the past, or what it was they told themselves time and again to "Never forget."

Ultimately, I've settled on an approach not entirely out of step with that of ZHP.

Try to do the right thing, and maybe, if you're lucky, it does the trick.

Or maybe it makes it the tiniest bit easier for someone else to get the right thing done for real.

Maybe it just takes that miniscule slice of the universe under your direct control and makes it the slightest bit better for the people passing through. And even on the off-chance it doesn't, at least you tried to be part of the solution instead of part of the inertia preventing a solution from happening.

You can do it hopefully, you can do it desperately, you can do it out of spite, you can do it facing-god-and-walking-backward-into-hell-style, if you want.

It all has value. Maybe not a lot, but more than giving up. And any value, no matter how small, is still infinitely more than none at all.